LaChanté Mobley

Her judge wanted to give her 10 years. Instead, she got life.

LaChanté Mobley grew up in a devout Christian household in Springfield, Ohio, under her mother’s strict, disciplinarian hand.

From the age of seven, she wanted to be a nurse. “My dad bought me a little doctor’s kit, with a play stethoscope, and I loved the idea of helping people,” Mobley said. As she grew older, Mobley felt boxed in by her family's strong religious views. “I wasn’t allowed to consider the medical profession,” she said, “because you had to believe in God for the healing of your body.”

Searching for a taste of freedom, she moved out on her own as soon as she was able. But instead of independence, Mobley found herself in an abusive relationship with a man she describes as “ultra-violent.” In 1998, she gave birth to a son, Le’Marquis, who brought her great comfort and joy.

Pictured above: LaChanté with her mother.

In her mid-twenties, Mobley decided it was time to seek a fresh start, hoping to build a healthier life for Le’Marquis. She moved north to Jackson, Michigan, where she settled with her son and began working at a nursing home. Mobley had a particular gift for treating patients with dementia. “I could meet them wherever they were, even if they were living back in 1923,” she recalled. “If they were waiting for their covered wagon, I’d say, ‘Okay, if you put your shoes on, your covered wagon might come!’”

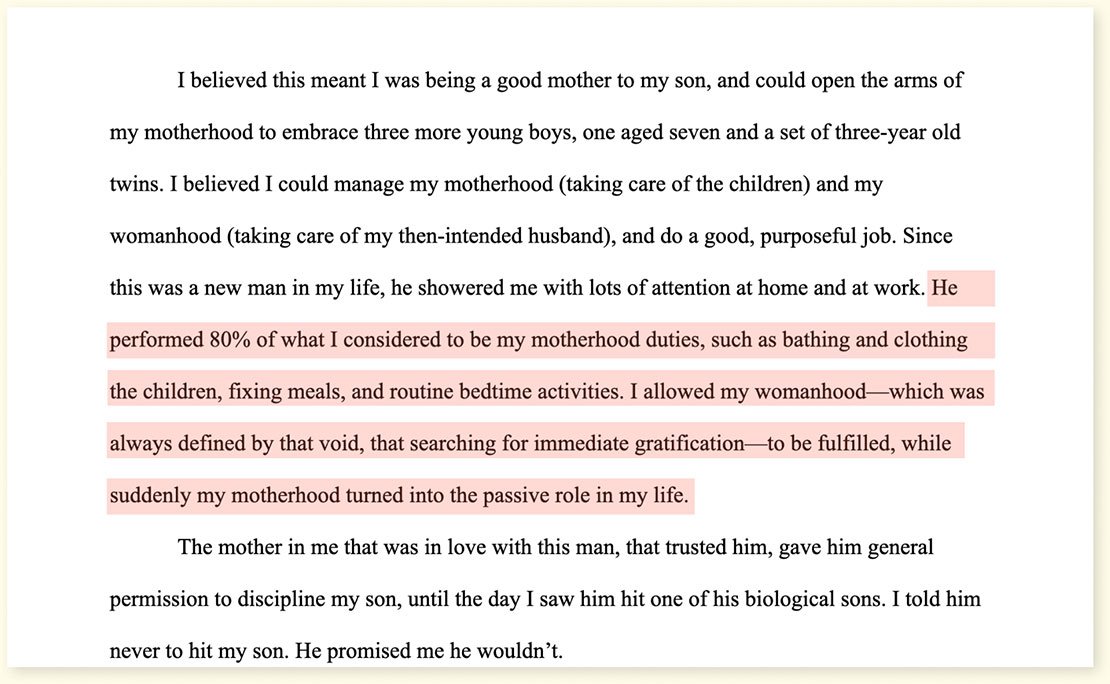

Right away, she fell in love with a coworker who had been assigned to mentor her. “This guy has a job and a lease and a car!” Mobley remembers thinking. When the pair started dating, he was unusually doting. “He’d rub my feet and cook dinner and get the kids ready for bed,” Mobley said. They quickly got engaged.

Read: Except from "Marred Motherhood," an essay Mobley wrote while incarcerated.

One day in December 2002, four-year-old Le’Marquis wet his pants—a habit Mobley had been trying to get him to buck. Mobley asked her fiancé to have a talk with him, but unbeknownst to her, he hit Le’Marquis with significant force. The next day, Mobley got up early and left for work. But by noon, she learned that her fiancé had taken the boy to the hospital, after he’d stopped breathing.

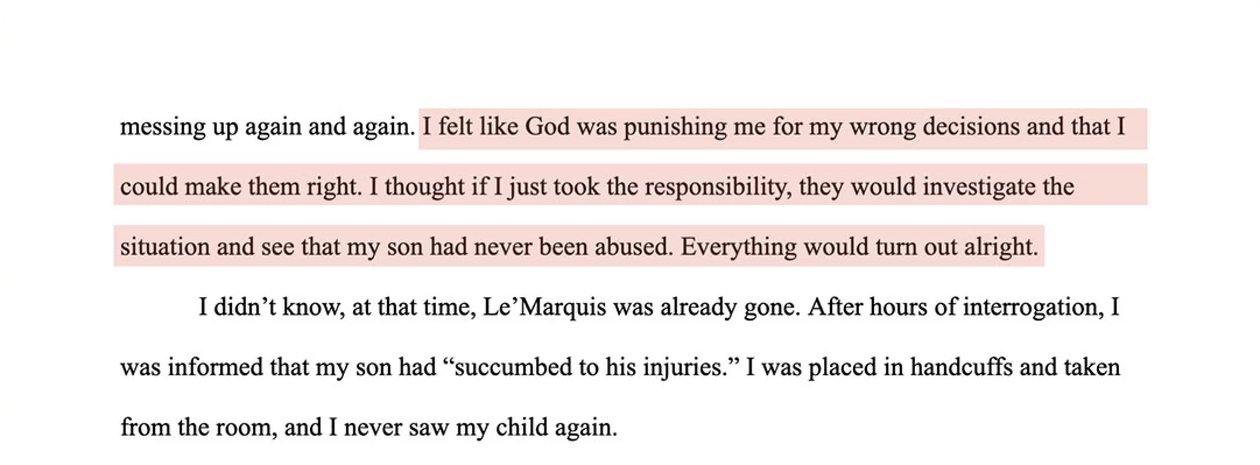

Hours later, according to Mobley, a detective told her that Le’Marquis had “succumbed to his injuries.” She fainted. The next thing she heard, from the floor, was: “LaChanté Mobley, you’re under arrest for the murder of Le’Marquis Hertford.”

Read: Except from "Marred Motherhood," an essay Mobley wrote while incarcerated.

Two years later, Mobley went to trial; she faced charges of first-degree child abuse, second-degree murder, and first-degree felony murder. It didn’t matter that, in the judge’s view, Mobley’s fiancé was the “person most responsible, the real actor.” Michigan’s felony murder law meant that she could be held liable for her son’s death. On June 19, 2003, a jury convicted Mobley of child abuse and felony murder.

It didn’t matter that, in the judge’s view, Mobley’s fiancé was the “person most responsible, the real actor.” Michigan’s felony murder law meant that she could be held liable for her son’s death.

It didn’t matter that, in the judge’s view, Mobley’s fiancé was the “person most responsible, the real actor.” Michigan’s felony murder law meant that she could be held liable for her son’s death.

Soon after, Mobley’s fiancé went before a separate jury. To the shock of the presiding judge, Mobley’s fiancé was acquitted of killing her son, and pled guilty to second-degree child abuse; he served a short prison term, and was released more than ten years ago.

When it came time for Mobley’s sentencing, she faced a different fate.

She was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole— the mandatory sentence in Michigan, and ten other states, for felony murder.

“Felony murder made the whole thing possible. It just takes away your discretion.”

– Judge Chad Schmucker

The case haunted Judge Chad Schmucker, who presided over both Mobley’s trial and her fiancé’s. Thinking back on Mobley’s sentencing years later, Schmucker said that if the law had given him discretion, he would have given her “much less, maybe 10-25 years – she’d be out of prison by now.” But because of Michigan’s mandatory sentence for felony murder – life without parole – he believed his hands were tied. “It was difficult to know that he gets out and walks and she stays in prison for life,” he said.

Mobley knew Schmucker’s concern was genuine. His own daughter served time in jail and was housed in “the same tank” as Mobley. “I want you to know that my dad asked about you,” Mobley remembers Schmucker’s daughter saying. “He wanted to know if you’re okay.”

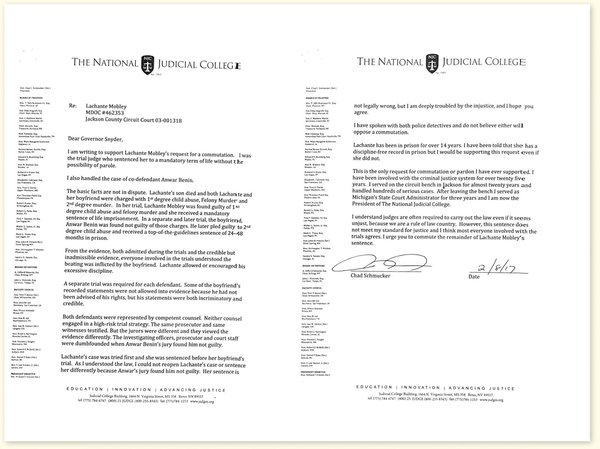

Though Schmucker had no way of revising Mobley’s sentence, he knew she still had a path to a second chance: a commutation of her sentence, which must be issued by Michigan’s governor. When Schmucker left the bench, he sent a letter about Mobley’s case to the governor, in support of her commutation petition.

“Her sentence is not legally wrong,” Schmucker wrote. “But I am deeply troubled by the injustice, and I hope you agree.”

The retired judge had never written a letter in support of a single person’s commutation or pardon, even after 25 years on the bench. But in Mobley’s case, he told the governor, “The sentence does not meet my standard of justice, and I think most everyone involved in the trial agrees.” He remembers discussing the case years later with the prosecutor and cops who helped put Mobley behind bars; they said they didn’t oppose a commutation either.

“Most judges want to have some discretion, but there are always efforts to take away that discretion,” Schmucker said. Once the legislature has set a high mandatory sentence for a crime—even a catch-all charge like felony murder, where each case’s underlying circumstances and each defendant's degree of culpability vary so widely—“it’s really hard to ratchet it back legislatively.” The only remedy, Schmucker says, is the governor’s power to commute sentences like Mobley’s.

- Listen: LaChanté thanking everyone and wishing everyone a good holiday.

In the years since Mobley was sentenced to life, she has become a leader at Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility, where she has taught mental health classes to her peers and served as co-chair of a committee to help abolish mandatory life sentences, through a nonprofit called the National Lifers of America. She has also become an expert food-services employee, a volleyball player, a poet, and a student of children’s literature. She is currently working on her first children's book, about two siblings who find and make a home for a turtle. (“My interest in children’s literature comes from my upbringing,” she said. “My siblings used to ask me to tell them stories at night, and I’d use my huge imagination to help me escape from the reality of my childhood hardships.”) Mobley has mentored many young women who’ve survived domestic violence. “As I listen to the women here,” Mobley said, “I hear so many situations in which a male counterpart did the crime, and he didn’t get locked up or did less time.”

Mobley’s commutation petition is currently under consideration. So far, she has served nearly 22 years of her life sentence.

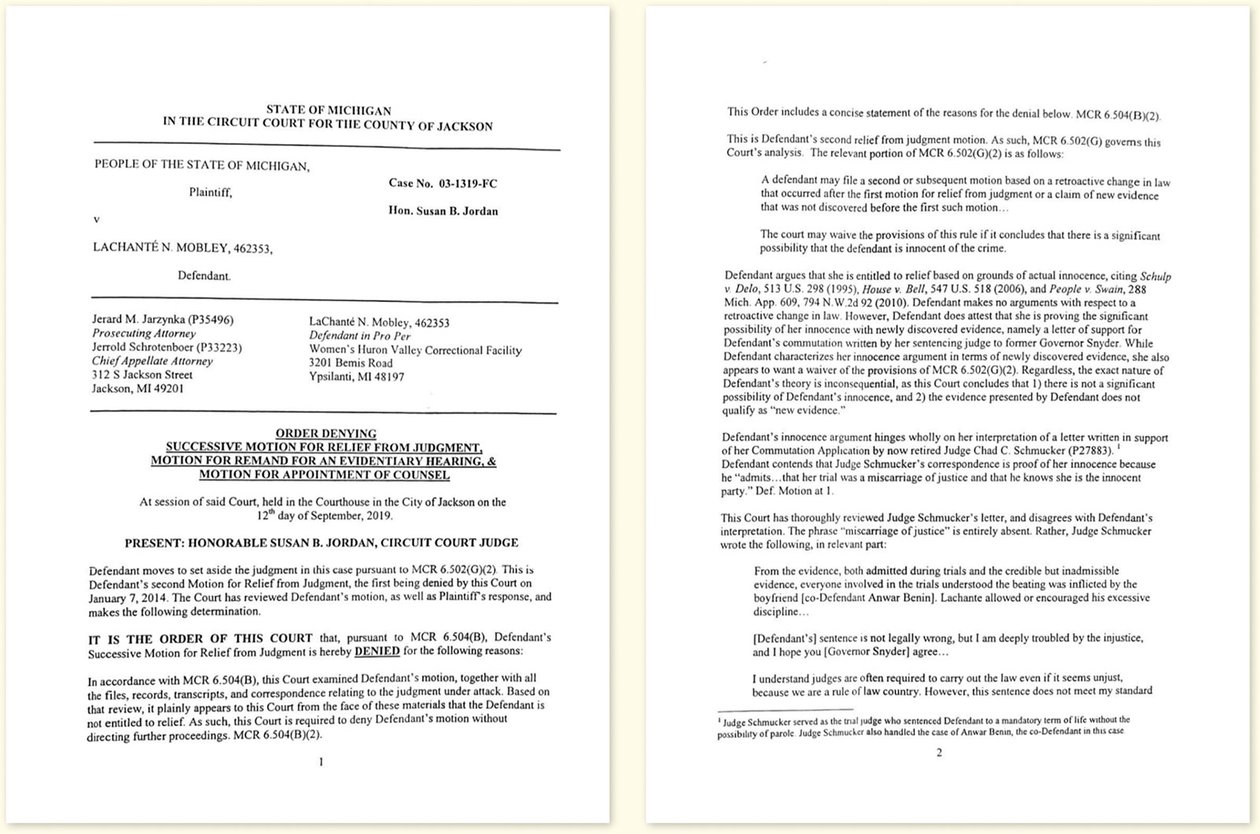

Discover: The order denying successive motion for relief from judgement. The motion asked for remand for an evidentiary hearing and motion for appointment of counsel.