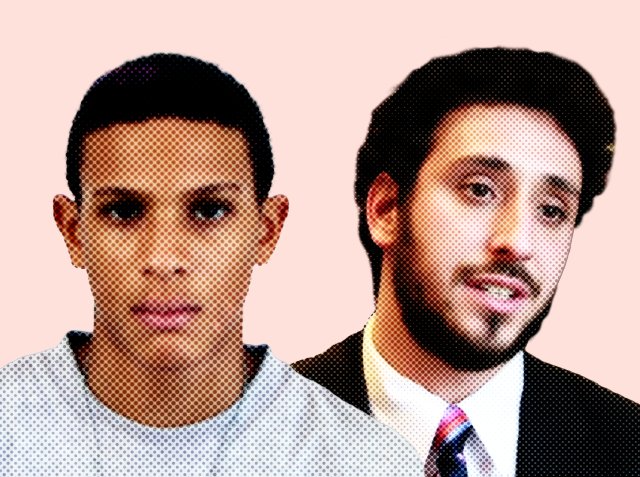

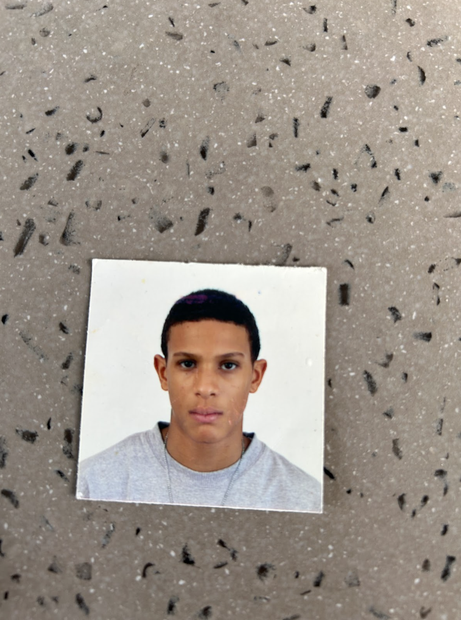

Sadik Baxter sat in handcuffs in the back of a sheriff's vehicle Miles away, his friend hit two bicyclists with a car.

Sadik wasn’t present at the scene of the crash, but he was charged with two counts of first-degree murder.

Read Sarah Stillman’s investigative reporting on felony murder in the New Yorker.

"Sentenced to Life for An Accident Miles Away" features Sadik’s story and the nationwide data findings and stories from the Felony Murder Reporting Project. Continue scrolling for more on Sadik's story and the Project →

When Sadik was twenty-two years old,

he was the victim of a nightclub shooting, which lodged a bullet in his lower back. He took Percocet to manage the pain. Soon after, Sadik’s mother died of lupus, at fifty-nine; he fell into a deep depression after losing her. Two years later, he was struggling with addiction. His bright spot was his four-year-old daughter.

On August 3rd, 2012, when Sadik was twenty-five, he took his daughter to Baby Ideal, to pick out an outfit for her first day of kindergarten. He remembers feeling proud of how much his daughter had grown.

But the next night, Sadik made a bad decision that he would replay many times over the next decade.

He and his friend, a talented twenty-six-year-old singer named O’Brian Oakley, went out to a suburban Miami casino. The pair drank heavily, and Sadik took a Percocet, too. After losing cash at the blackjack table, Sadik left with O’Brian; soon after, Sadik had an idea: to offset the losses, he could steal from unlocked cars in a wealthy neighborhood nearby.

Just before dawn, Oakley drove, reluctantly, to Cooper City with Sadik.

While Sadik tested the handles of parked cars, grabbing whatever minor items he could find, O’Brian waited in his silver Infinity around the corner. Sadik was grabbing some loose change and a pair of sunglasses from a black SUV, when the car’s owner confronted him. O’Brian, in his car, fled the scene.

The stranger called the cops. Several minutes later, Sadik was arrested and handcuffed.

Moments later, O’Brian, who’d gotten lost trying to leave the neighborhood, accidentally circled back. This time, he was pursued by sheriff’s deputies. During the high-speed chase, O’Brian ran a light and was struck by another car; his vehicle spun out of control, and fatally struck two bicyclists, Dean Amelkin and Christopher McConnell. Sadik was several miles away in the back of a deputy’s vehicle.

The central parties involved agreed that neither Sadik nor O’Brian intended to hurt anyone, and that Sadik was nowhere near the crash.

Trial transcript of the man who called the police on Sadik, for stealing loose change and sunglasses from his unlocked vehicle.

Here, the man acknowledges that Sadik was not at the scene of the crime and could not have killed Dean or Christopher.

Nonetheless, prosecutors used the felony murder doctrine to charge both men with first-degree murder.

Convicted, they’re now serving mandatory sentences of life in prison without the possibility of parole.

“I’m tasked with following what the law is, and the law in itself, good, bad, or indifferent is enacted by the legislature.”

– Judge of Sadik and O'Brian’s trial

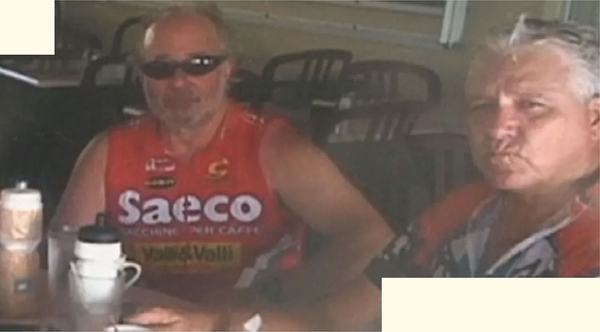

The three children of Dean Amelkin, one of the victims – Ian, Brett, and Chelsey Amelkin – came to both young men’s defense in court.

Ian wrote a letter to the court, arguing, “This sentence is cruel, unusual, and in time will be considered unconstitutional.”

Denise McConnell, the wife of the other victim, told the Felony Murder Reporting Project that she was also shocked upon learning of Mr. Baxter’s sentence. “I didn’t know it was mandatory,” she said. “I don’t think he should be in there for life.

“Now four lives— my dad’s, Mr. McConnell’s, Mr. Baxter’s, and Mr. Oakley’s —are forever destroyed by the events of August 5, 2012. I express my deepest sympathies to Mr. McConnell’s family and hope that this trial and sentencing helps bring closure for their loss, as well as to my family members present in the courtroom.”

– Ian Amelkin

Ian Amelkin, the son of Dean Amelkin, one of the two cyclists killed. Source, NYU School of Law.

THE FELONY MURDER REPORTING PROJECT

For decades, felony murder has been a black box – no one knows how many people around the U.S. are incarcerated using the doctrine, often for life. We set out to investigate.

Over the last two years, we unearthed more than 10,000 felony murder cases across the country, including more than one hundred in which the person charged with the murder did not kill or intend to kill. Yet the majority of states still remain unreported.

Our goals are to spur more informed national and local reporting on felony murder cases; to encourage more robust data-gathering on the issue and analysis on its diverse impacts; and to contribute to the general public’s awareness of the legal doctrine.

What is Felony Murder?

Definition

At its broadest, the felony murder doctrine allows for people to be charged with murder if a death occurs during the commission of certain felonies -- regardless of whether or not that death was intended.

Effect

- Felony murder sentences people to life – and, in rare cases, even death – for murder in instances that would not have otherwise been considered murder for the person convicted.

- People who may have been present at the scene of a felony – but who did not cause or participate in the actions that led to a death – can still be charged with murder.

- In some instances, such as the case of Sadik Baxter, a person can be charged with murder for a killing at which they were not physically present.

- Often, prosecutors can charge a higher degree of murder on account of the doctrine, sometimes resulting in a sentence of mandatory life without parole in certain states.

The State of “Felony Murder”

Felony murder charges are widespread in the United States. Forty-eight out of 50 states, as well as the District of Columbia and the federal government, allow people to be charged and sentenced using some version of felony murder.

Explore how felony murder works in your state:

National Patterns:

Nineteen states make it even easier for prosecutors to secure the harshest of convictions with multiple overlapping laws and degrees of murder or homicide from which they can choose.

Ohio, Virginia, New Hampshire, Mississippi, and Louisiana have three different laws each. Florida has four.

9 states, at least, as well as the District of Columbia, explicitly authorize homicide convictions for accidental overdose deaths.

Thirty-four states, as well as the District of Columbia, authorize the death penalty or a sentence of death-in-prison (life without the possibility of parole) for a death that occurs that the defendant had no intention of committing.

Under the so-called “proximate cause” theory, 19 states allow people to be convicted of murder even when neither they nor any of their co-defendants killed anyone, but instead, a third party (i.e. a police officer or a store owner) was responsible for the death. Other states follow the “agency theory,” requiring that at least one of the co-defendants take deadly action.

Just over a dozen states allow individuals a way to defend themselves from being held accountable for a death under the felony murder rule. Ten states allow a person accused to set forth an “affirmative defense,” and 11 states require that the prosecution actually prove that an individual had some level of awareness– intent, knowledge, or other mindset–that a death would or was likely to occur.

This map draws upon state-by-state legal research by The Sentencing Project; Caitlin Glass and her team of researchers at Boston University; students from the Movement Lawyering Clinic at Howard University School of Law; and students from the Investigative Reporting Lab at Yale.

Four Investigative Findings

Over the past two years, we spent more than 1000 collaborative hours unearthing and analyzing more than 10,000 cases nationwide, examining race, gender, age, and other variables. Although most states keep little to no data on those serving prison time for felony murder we were able to analyze data in 18 states, 11 of which we were able to independently verify were as close to complete data sets as possible.

Our investigation revealed four fundamental and troubling patterns within the felony-murder prosecutions we examined.

Here’s what we learned:

1. Even greater disproportionate impact

Felony murder is a significant driver of the extreme sentencing of youth, Black people, and women (including survivors of domestic violence and police violence), and an overlooked driver of mass incarceration.

2. Excessive punishments

Felony murder drives many of the lengthiest and most inequitable sentences.

3. Lack of data

Across the 48 states and Washington, D.C., there is a profound lack of transparency and consistency in the data on felony-murder charges and convictions.

There is no complete national data on felony murder. While felony murder is a significant driver of extreme and disproportionate sentencing in America, most states keep no clear data on felony murder convictions.

4. Distorting power of plea bargains

We are collecting stories–in addition to data–to better understand how the felony murder rule impacts people across America. We spent months connecting with people currently incarcerated for felony murder, family members of both those incarcerated and those whose lives were lost. This is just the start.

In the World

The Felony Murder Reporting Project has become a critical resource for journalists and advocates across the country. Our findings have appeared in local and national publications, including HuffPost, The Hill, and Columbia News Service. Additionally, our data and analysis have been cited in filings before both federal and state courts.

News

Litigation

The Lack of Data

Despite the prevalence of felony murder, the full picture of who is incarcerated for it, how often, and why remains unclear. We hope to get a fuller picture, too, of the diverse perspectives and experiences of crime survivors.

Visit our State Data Pages to explore our findings and also learn more about what data collection looked like state to state. Visit our Methodology page to learn more about how we arrived at our findings.

What Can You Do?

We’ve started a database of felony murder cases that reflect meaningful trends. Reach out for more information on how to investigate and write on these cases, or how to pursue data reporting in jurisdictions that interest you.

Contribute to our public GitHub repository, add to our tracker of state data resources, or contact us to request access to our code and the state-by-state raw data we’ve collected.

Do you teach or participate in a law school clinic? Need a topic for a research project? Are you part of an academic institution? Get involved in assessing the scope of the felony-murder rule.

Do you or a loved one have personal experience with felony murder? Are you interested in learning more about the organizations working on different cases and reporting out stories? Please reach out to learn more.